Danse dans les Nymphéas: Immersive Exhibitions, Multimedia Art, and Making Impressionism Fun

Joey Wawzonek

One of the weirdest consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a fundamental shift in how art can be and is consumed. The pre-vaccine pandemic prohibited the perusal of physical artworks since galleries are enclosed spaces which, at times, necessitate a close proximity with others outside of your cohort. With how stringent the atmospheric conditions are in most galleries, the idea of introducing additional moisture through people with COVID-induced sniffles was certainly a concern for many curators. With the rest of the world moving to primarily online modes of functioning, the realm of art followed suit with a greater focus on digitisation and accessibility. With a 77% drop in museum attendance in 2020, cultural spaces were afforded the rare opportunity to strip the walls of famous works so they could be catalogued more extensively, scanned in higher quality than ever before, and be presented globally over the internet.[1] As a part of Google’s own AR initiatives, paintings and sculptures could be virtually projected into one’s own home to impart a sense of scale, and to allow viewers to get incredibly close to the artwork.[2]

These searchable catalogues and viewable works are great in theory, particularly from an accessibility standpoint, but the glut of artwork available means a lesser focus on the provenance of particular works and artists, and a consumption pattern akin to scrolling through an Instagram feed. One of the most important parts of the gallery experience, personally, is the contextualisation of more renowned works amongst similar pieces which are largely omitted from the cultural canon. Why should these specific works by Degas or Warhol or Vermeer be so celebrated, so singularly highlighted? This digitisation and the general accelerationism induced by COVID only exacerbates this problem. If I have access to all this art but no guidance, no structure to appreciating it, then I’m just going to look at the artists I’m aware of and look at their work, like those who enter the Louvre and beeline it to the Mona Lisa. In most cases these people don’t care about the context of the work, just that they saw it. Perhaps this isn’t intrinsically wrong, but it is certainly a vapid means of consumption, focusing on clout over appreciation.

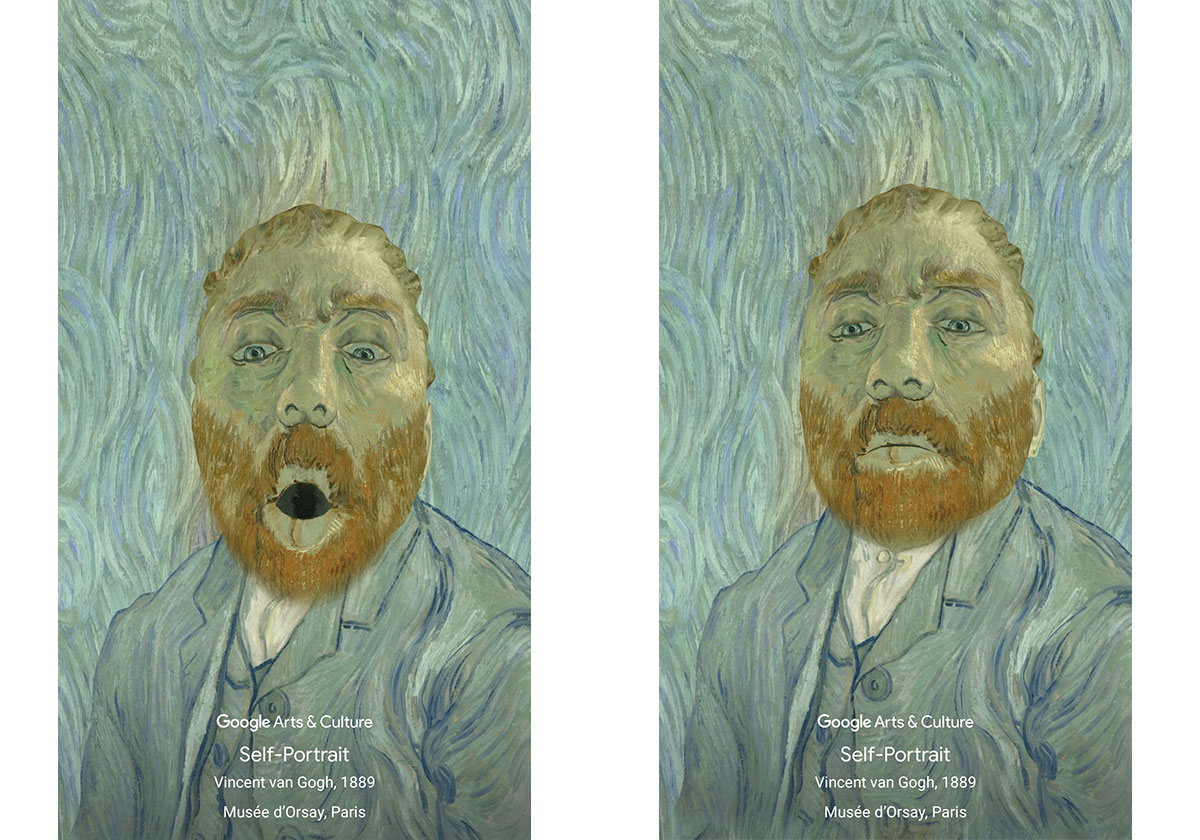

When restrictions did ease up in the second-half of 2020, the spaces which were available for much of the world were more open environs where physical distancing was easy and air circulation was better. It was about this time that ‘immersive exhibits’ exploded in popularity across North America and Europe. Largely hosted in industrial spaces, these shows permitted distancing through projections of works onto the walls of a space, creating an ‘immersive experience’ by having attendees be subsumed by an artwork or its constituent components. There’s an argument to be made that 2020’s Netflix series Emily in Paris aided the exponential growth of these shows as a consequence of the Netflix Effect, but even with this as a contributing factor, the omnipresence of these exhibits seems inexplicable.[3] Nonetheless, the directors of these shows and artist foundations have claimed that this maximal approach to the works of Vincent van Gogh in particular assist in understanding the artist on a more personal level, as if viewers will see the world as the artist did, will understand the machinations of his mind prior to his death.[4]

Even ignoring the fact that this is an impossibility, to understand the lived experience of another, this perpetuates a masturbatory romanticisation of the tortured ‘other,’ without engaging with their purported experience in a critical manner. This ballooning of the work may induce a sense of being ‘inside’ the painting, but it also means turning the work of an artist known for their impasto (thick application of paint, creating depth) and its consequent dimension into a flat image. Beyond this, the poor quality of a projected image in relation to a physical work means those brushstrokes won’t even appear on the walls of a space, just as they won’t on the screen of a phone.[5] The raw unmixed pigments of (post-)Impressionism similarly cannot be well approximated through a display. My problem with these exhibits is not with idea of simulacra of the works themselves, but with this glorified and yet dehumanised reproduction, claiming to be focused on the personal history of the work while losing the humanity and physical deliberation of the paintings’ creation. The immersive experience has nothing to do with the works themselves, but with the idea of the work, allowing us to say we were there rather than we saw and understood.[6] In the wake of the success and proliferation of these van Gogh shows, we are now inundated with these $50 multi-sensory experiences for Klimt, for Monet, for Chagall, for Picasso, for Tutankhamen, for Frida Kahlo (who surely would have loved the commodification of her work for vapid consumption by white people). The presence of pre-recorded vague statements and the wafting stench of cypress brings as much to the experience of viewing these low quality images as South Park: The Fractured But Whole‘s Nosulus Rift did by letting you smell farts. These shows claim to complement the physical gallery experience but they merely detract and obfuscate. What impetus is there to gaze upon a work in person when influencers claim this is superior to the rinky-dink painting, when one can state with the authentic belief that they have already seen it, when you can go do yoga in a painting?[7]

With it made abundantly clear now how detestable the idea of the immersive experience is, how can fine art be made approachable, educational, engaging, and informative of its context? One possible answer lay in the humble CD-ROM.

Impression, CD levant

The accessibility of visual resources afforded by CD-ROM multimedia software cannot be understated, but the educational potential therein is generally bound to encyclopedic entries and nested hyperlinks. For the scholar, this is more than enough. The CD-ROM represents a means of quickly consulting a piece of information and its associations.[8] Without guidance or purpose, however, educational multimedia is functionally identical to an encyclopedia — partaking of it might bestow knowledge, but without structure it is entirely up to the user to wield this tool effectively. As far back as 1988, Doctor of Education Richard J. O’Connor hypothesised the need for both structured program content and user control working in harmony to effectively teach art history via CD-ROM.[9]

Curated collections certainly helped the curious dip their toes into art history, in the same way that exhibitions in a museum would. Corbis Publishing’s 1995 A Passion for Art was a prominent example of the multimedia presentation done well, lauded by the press and academics alike for its ease of use, breadth of content, and demonstrations of Post-Impressionist artistic developments.[10] For a brief moment in time, these interactive exhibition CD-ROMs were a lucrative venture. Centre Point Software out of London reported an 80% increase in sales for them from October 1994 to June 1995, and Montparnasse Multimedia’s Le Louvre: The Palace and Its Paintings sold 40,000 units in France alone in the first half of 1995.[11] Not only did these discs bring the gallery or archive space home, but abroad. A touring exhibition might visit select urban centres, but a CD-ROM could be sent and accessed the world over. But outside their initial novelty, they remain educational tools. Well-guided ones to be sure, but perhaps lacking in engagement for a younger, less interested crowd.

Enter the fine art computer game (or, more appropriately, the Impressionist fine art computer game). Be it to raise visual interest, an approachability of form, or a more compelling, personal narrative through-line, Impressionist art has received far more attention in the space of games. Such reasoning is fair, as the artists’ rejection of École des Beaux-Arts traditions lessens the need to present a total history of academic painting. Their departure from accurately representing reality is more conducive to restrictive computer graphics. The relevant figures are named, known, and can be presented as grounded characters. Though the same rationale could be applied to contemporary immersive experiences, what these gameified works have going for them immediately is that they aren’t trying to pass themselves off as some truest means of taking in the work of an artist, nor the artists themselves.

Night Café

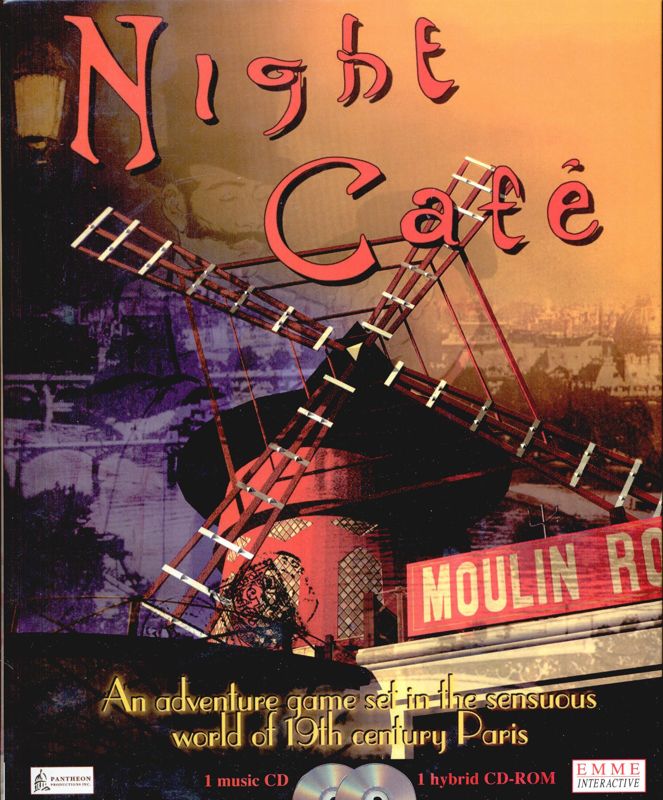

One of the first games about Impressionism, 1997’s Night Café, developed by Pantheon Productions Inc, published by EMME Interactive SA, plops the player into the dead streets of Montmartre. Through light adventuring across seven locales, the smooth narration provides somewhat vague context for the relevant people and places visited in overcast renderings of Haussmann’s Paris. Charming as it is, the voice work falls short in respects to explaining the context of Impressionism and the Paris art scene. This leaves any factual information in the realm of cute trivia and pleasantries about who knew who, and how the brush met canvas. The characteristics of Impressionism are clear therein, but not the purpose.

Weak too is the gameplay, a set of light puzzles which consistently rely on guesswork and brute force — not because they are difficult, but because it is frequently the only option. On tile puzzles, paintings are reconstructed on a 3×3 grid with sliders that change random tiles besides the one that is highlighted. On reconstructions, figures are placed blindly into a scene. When sequencing a series of works, the barest hints of sketches in a previous room are of no help for the works in question are minuscule icons, and there is no consequence for matching every possible painting with every possible frame. Not that the puzzles themselves teach anything in the slightest, they are but busywork, granting access to an artist’s gallery once checked off.

Where Night Café shows promise is its approach to presenting a historiography. When not listening to the narrations, the main text of the game is delivered via personal correspondence and newspaper clippings. Through this, the emphasis on how the Impressionists knew one another (or those important to their oeuvre) begins to make sense, and the player is situated more firmly in this sliver of time as was experienced by the subjects. This has the benefit of avoiding overt historical analysis, but the texts which are chosen nonetheless promote a particular reading of the works, one which is separated from the contexts of art history itself. The paintings become quaint symbols rather than important monuments.

Works like Manet’s Olympia are said to be historically important within the body of the game, but at no point is it related to the player why that is the case. Even the in-game dictionary (more an encyclopedia) is of no help, acting instead as a long-winded conveyance of information provided elsewhere in this digital Montmartre. This comes across as further squandered potential, the opportunity to have the main thrust of the game concern primary sources, with secondary sources and analyses in this auxiliary space.

Despite its numerous shortcomings and lack of substantive value for those not already familiar with the subject matter, Night Café is undeniably charming. The few reviewers who ever touched on it agreed that the educational value therein was too light to make up for the weak adventuring, and vice versa.[12] Nonetheless, as an early glimpse into the possibilities of engaging actively with Impressionism through computer games, it demonstrated potential and a reality wherein the situation could only improve. The painted surface had been brought closer than ever through its digitisation. To come any closer would be to step inside the frame itself.

Mission Soleil

Developed and published in 1998 by French multimedia studio index+, Mission Soleil immediately stands apart from Night Café through its central conceit; the majority of the gameplay occurs within paintings, rather than the art being an accessory. The intro cinematic makes it evident that this is not the world of van Gogh, but some dystopic strangereal where the sun has gone out, taking with it the colour of the artist’s paintings.

Our first interaction is with an on-the-fritz robot who gives us a magical star and makes it abundantly clear that despite his algorithmic attempts at restoring the paintings, he crucially has never been able to see the paintings up close. When we inspect the sprite of Fourteen Sunflowers in a Vase, we are welcomed by a polygonal representation of the artist himself. Rather than be some depressed bastardisation of our posthumous reinterpretation of van Gogh, this avatar is almost chipper in his sun hat.

He invites us to use the magnifying glass button, and when we do we get an incredibly close-up look at the painting and the brushstrokes on the canvas. A 115MB title from twenty-five years ago renders this human aspect more concrete than the supposed technological marvels of our present day can. Furthermore, you can click another button to have van Gogh hold up the painting so you can understand its scale.

Walking through the exhibit space, not only are the walls a disgusting hue of dentist-office beige, but they are dirty and in disrepair. The paintings are grey-scale, and even the vases which should be abound with almond blossoms are little more than collections of gnarled branches. Clicking on these paintings transports the player into them, and here they are shown in colour. The subject matter is rendered in three-dimensions and the player can move their perspective to see beyond the confines of the frame. What is particularly endearing about this is how the dithered textures impart a quasi-Impressionist feel despite being a limitation of technology. Instead of hearing lilting violins, the soundscape is realistic. Roosters crow, the wind blows, leaves tumble to the ground. In each painting you need to find an object to restore the colour, and certain interactables help you proceed.

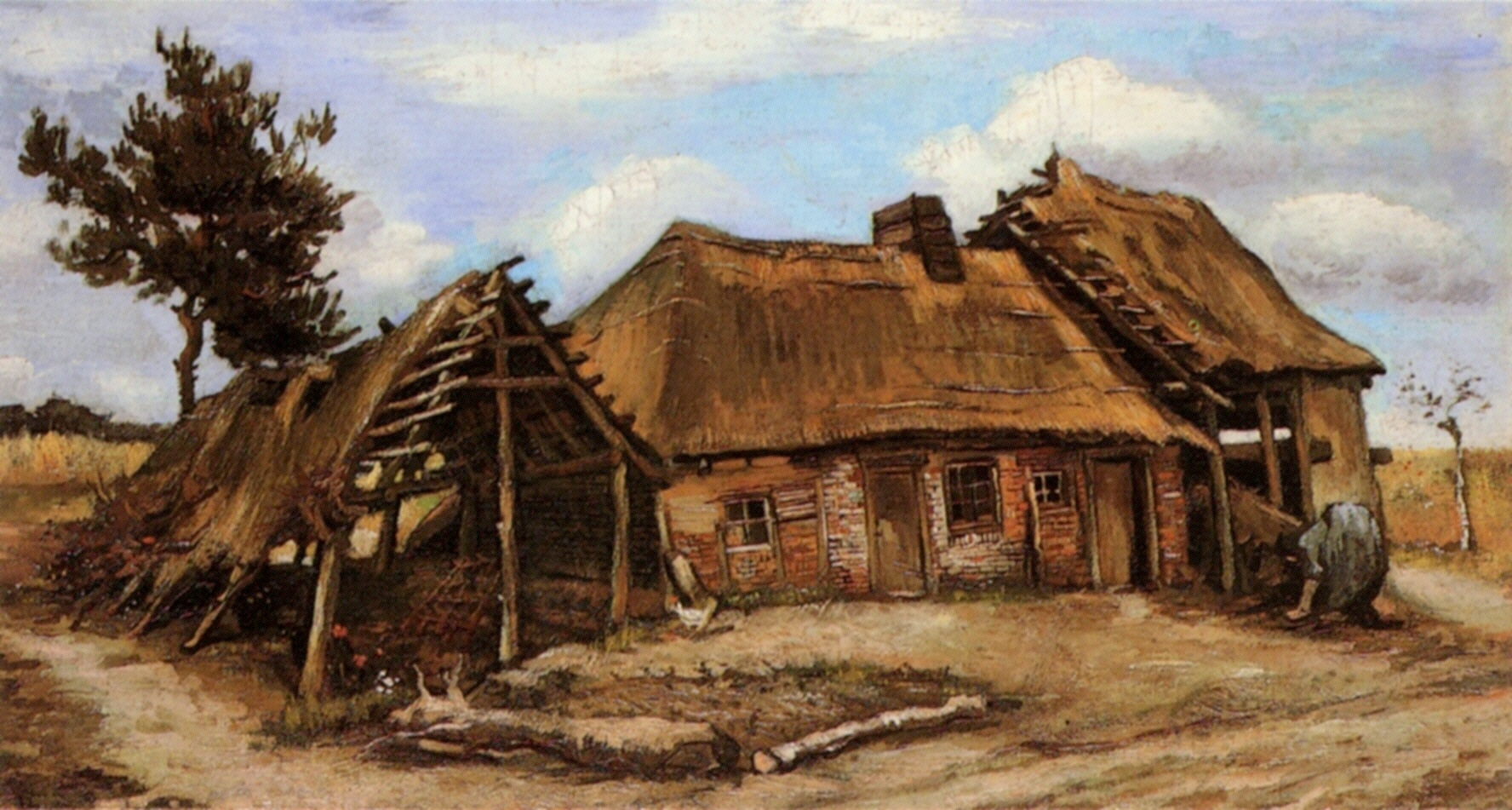

For Cottage with Decrepit Barn and Stooping Woman, one can actually enter the slanted building only for the interior to be the selfsame from The Potato Eaters, with the table embodying Still Life with an Earthen Bowl with Potatoes. Obviously some liberties have been taken in order to create these more singular, cohesive spaces, but it helps to demonstrate that these paintings were not created in a vacuum, and in fact were inspired by similar, if not identical, settings. These early works are of the same earthen hues in game as they are in reality, contrasted against a gorgeous blue sky.

Finding a potato for Still Life with an Earthen Bowl with Potatoes bestows upon us an educational tidbit of context, that still life paintings are historically flowing with finest dining ware and ostentatious displays of food, representing wealth and bounty. We swirl around Jan Davidszoon de Heem’s Still-Life with Fruit and Lobster before van Gogh tells us his desire to show the food of the poor and demonstrate this connection between dining ware from the earth, and tubers from the earth in a display of realist honesty. Restoring The Potato Eaters tells us that it is difficult to break with what you have been told to do.

Though this is obviously in response to academic traditions as taught to classically trained artists at École des Beaux-Arts, it resonates with me because of those immersive experiences. In a sense, those exhibits have broken with the expected, but they have also perpetuated that consumptive mode which snaps a picture and moves on, akin to an Instagram trap. In Mission Soleil, the tradition of the art gallery has been eschewed for a different maximal approach which at times demonstrates a falsehood about these works through the artistic liberties of an imagined 3D space, but by also teaching directly without shoving contexts onto a placard, a catalogue, or an art history education. Maybe this gamification of art is itself problematic too, but as an edutainment piece of software I am more forgiving.

When we venture into The Night Café, I am apprehensive because of my time with 2016’s The Night Café: A VR Tribute to Van Gogh. That grotesquerie attempted to bring multiple works into one space in a manner I would consider a failure, those other works detracting from the titular cafe. The scale of the people made it especially hard to immerse myself in, but thankfully Mission Soleil opted to remove those figures entirely. The geometries here are simpler and more angular, but it weirdly works. Instead of the yellow smears of smooth brushwork in A VR Tribute coming off the lamps, Mission Soleil‘s lamps take the actual brushwork of The Night Café and turn them into quasi-3D sprites. A VR Tribute is a strangely disconnected sensory experience. Mission Soleil inundates the player with the din of cafe culture, clocks ticking away incessantly, indistinct conversation washing over us.

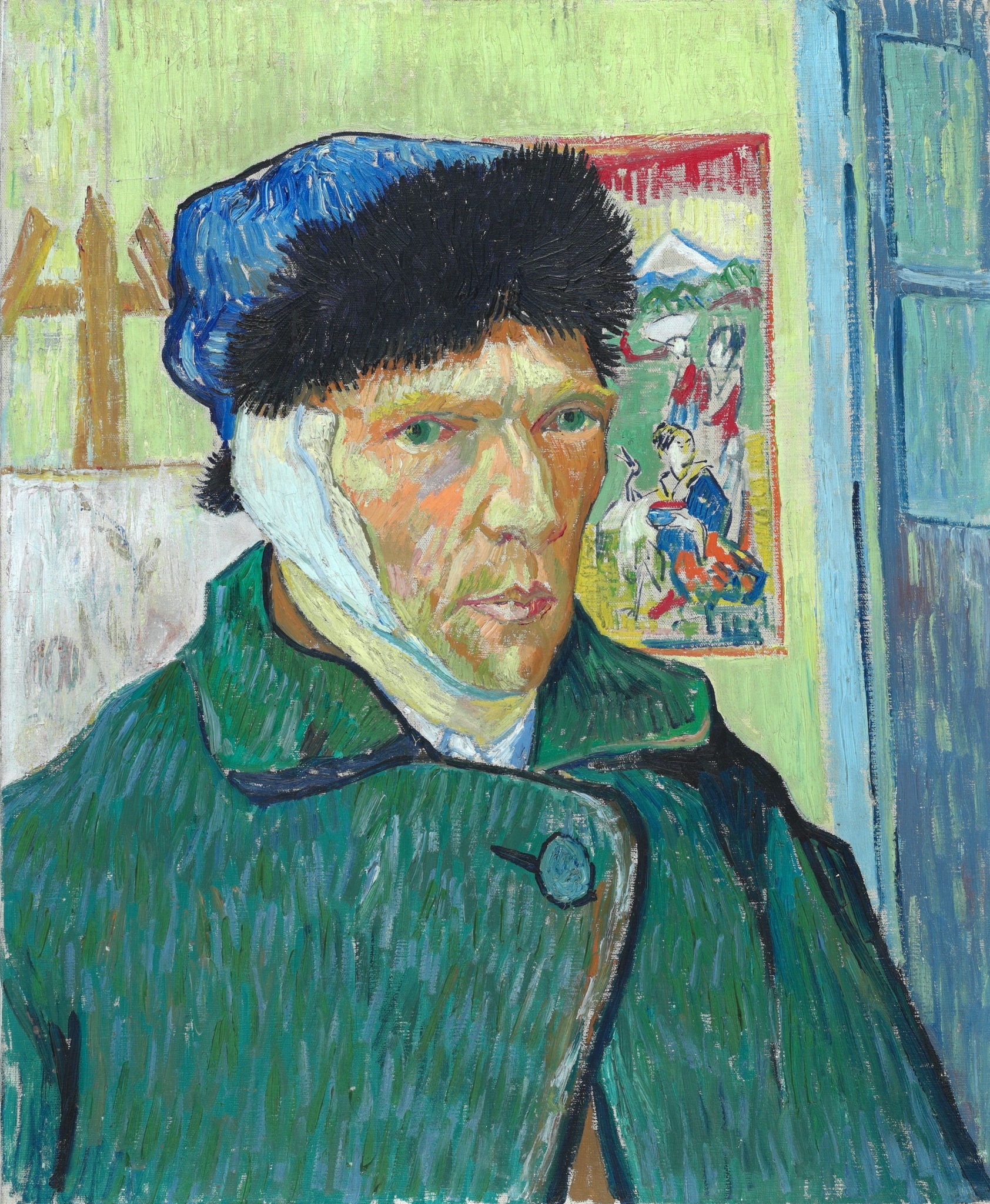

The later part of van Gogh’s life is, understandably, much less depressing here than in reality. Stepping into the Hospital at Arles series, we can hear the anguished cries of the patients who are again not depicted, but the commentary avoids sounding overly downtrodden. Van Gogh himself speaks of the proliferation of Japanese art and Japonisme when we restore Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, rather than wallow in misery. Ward in the Hospital in Arles’ commentary touches on the unappreciative response to his art, but in an informative manner.

We see van Gogh not as a man defined by mental illness, but simply as a man who wished to paint. Though this is painting too simple of a portrait in many ways, it also helpfully avoids the pratfalls of the contemporary imagining of van Gogh.

Mission Soleil warms the cockles of my heart in a way I didn’t expect it to at all. It is simply a good piece of edutainment software which is informative in a way one might not expect of a children’s approach to art history. It is refreshing and truthfully immersive in rendering paintings as physical spaces, rather than as flat images on a wall. It evokes an honesty to the painted work that is astounding for 1998, and serves as a phenomenal alternative to AR experiences or digital catalogues. This is a work which expects wilful engagement, and rewards it handsomely. From what media coverage is available, it did well with its target audience of 8-13 year old children. Kid Screen, an Italian awards group organised by Associazione Digital Kids and Direzione Generale Cultura della Regione Lombardia, awarded its premiere first prize to Mission Soleil, claiming it fully realised one of the more important functions of interactive multimedia: to present the user in a place that is enjoyable to be in beyond the functions performed in the program.[13]

Devoid of life as these spaces are, they feel real, lived in, and impressed upon. The journey is not accompanied by melodies imparting an emotion, or a narrative beyond the central idea of gathering sunflowers and restoring pigment, yet the throughline is compelling. From the humble beginnings in Nuenen, to his prolific time in Arles, to his final days in Saint-Rémy and Auvers-sur-Oise, the painted surfaces become the text themselves. This is not teaching about painting, but teaching through it.

Monet: Le Mystère de l’Orangerie

For their next Impressionist foray, index+ opted for a greater emphasis on adventure. 2000’s Monet: Le Mystère de l’Orangerie places players in the more grounded works of Claude Monet under the guise of helping him realise the architecture of Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris’ Jardin des Tuileries (presumably in the role of Camille Lefèvre). Starting in Monet’s home in Giverny, we learn of the oil baron villain’s plot to destroy the building to build a derrick. The journey through painted spaces is thus incidental, looking as if painted by Monet because it is a game about him and his work, not because we are actually in his paintings. More grounded, certainly, but ostensibly less charming.

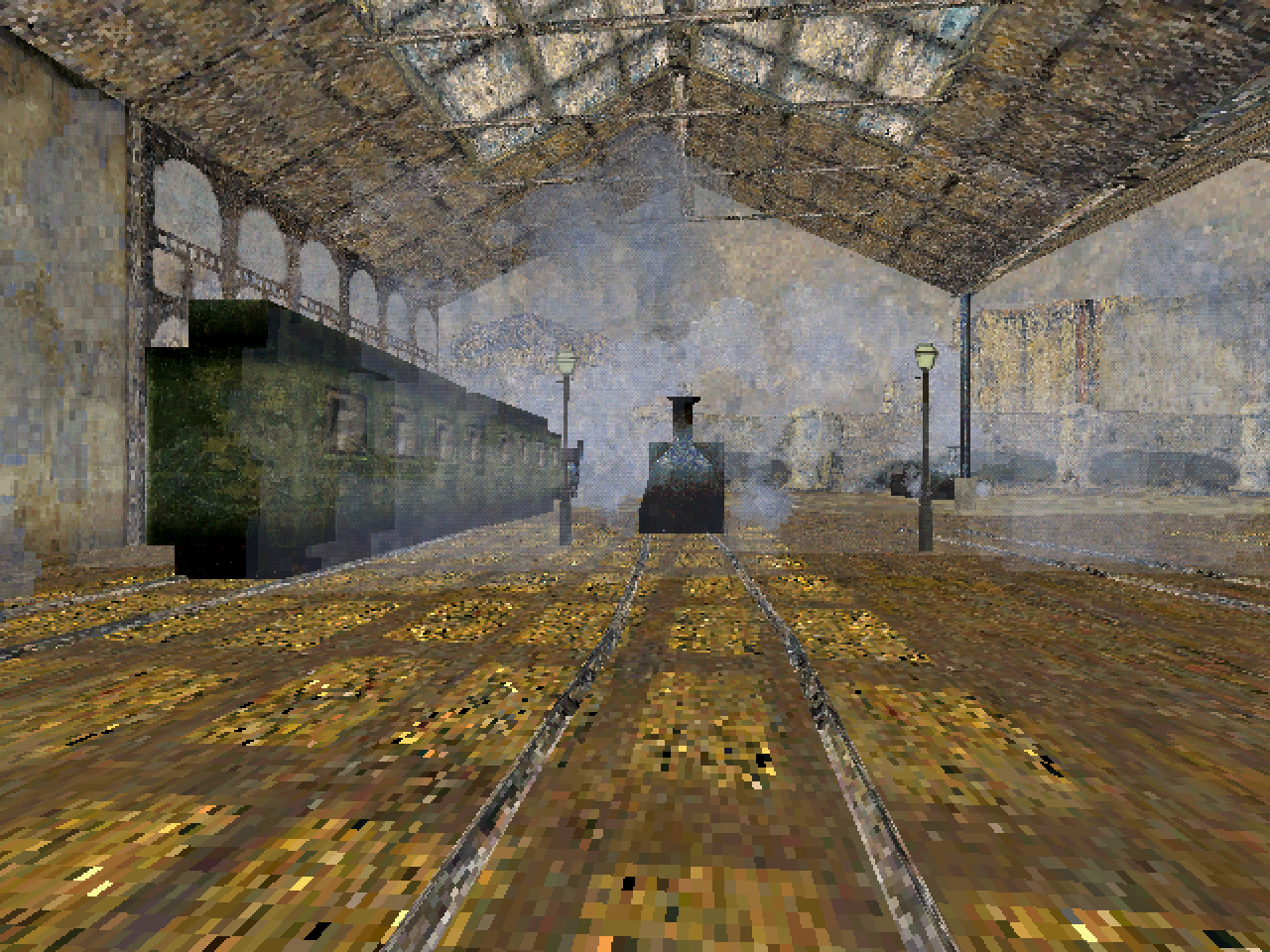

From the port of Le Havre, we escape over the rooftops onto a handcar to a snow blanketed Argenteuil. Through typical ADV logic, one can only board the train to Rouen by getting change for a ticket by purchasing roast chestnuts, though the change is stolen by a magpie who sits across an icy stream which is crossed with a piece of broken wood, and the train station attendant has fallen asleep and must be woken by the train’s whistle. On a time limit. While it is no doubt cute to adventure within these quaint landscapes, it is a disruption of the serenity seen in Mission Soleil. In Rouen we find a clown is in cahoots with the antagonists, pilfer a film reel from a caravan’s wheel, loot dynamite after hiding in a cupboard, and escape the police on a pedal cycle. Through the aforementioned film, we learn of Monet’s fascination with Rouen Cathedral’s façade, a brief but welcome interruption of the gameplay to deliver educational value.

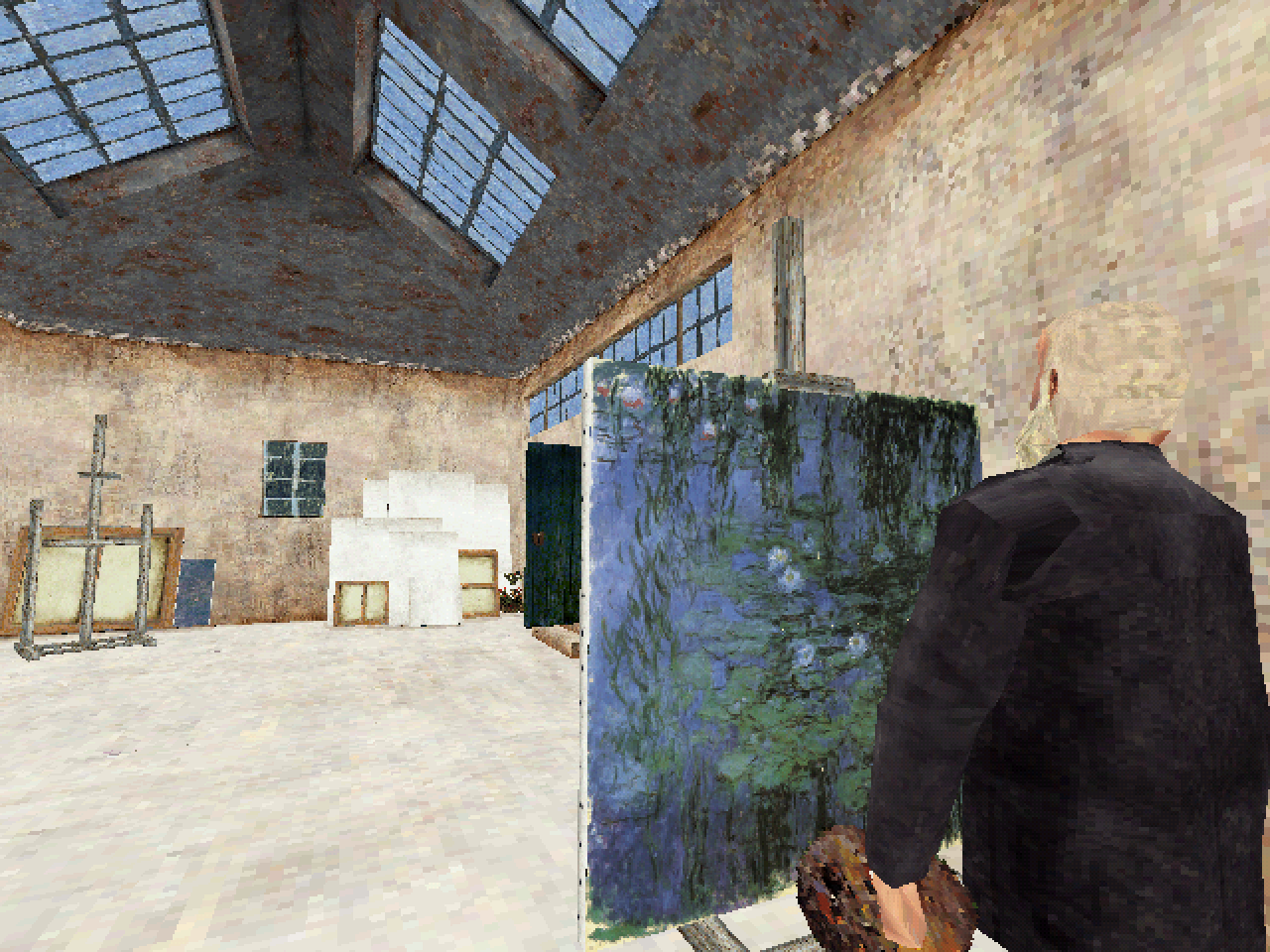

Upon arrival in Giverny to meet Monet face to face, we see his canvases for the first time strewn about his studio. While finishing Nymphéas bleus, Claude invites us to look at the works on display. This is the only time we learn anything about his art. His brief narrations explain the likes of La Japonaise and La Promenade, the influences of Japanese art and desire to capture a moment in time respectively relayed to us. A few issues arise.

Unlike Mission Soleil, there is no opportunity to view the canvas more closely, nor see its relative size. The latter is technically less of an issue as they occupy the appropriate amount of space in the game world, but without seeing Monet’s wispy brushstrokes, much of the magic is lost. Furthermore, these inspectables represent a minute fraction of his catalogue, with some particularly notable works relegated to duty as explorable environs. The effect of these locations is no doubt stunning and well realised, but it robs players of the opportunity to hear more about the works.

Before long, Monet is bound and gagged, a painting stolen, and we are fishing a key out of a pond, then making a mad dash to Paris to tunnel under l’Orangerie (which has a sniper on its roof) so we can defuse a wad of dynamite. The day is saved. The reward is that it is over, and we can view Monet’s work in the Gallery. Just as in Mission Soleil, we can inspect the work up close and view a size comparison. We may also click on a work to be taken to the in-game space where it resides, or where a location has been inspired by the work. It is magnificent to see this return and be expanded upon through those click-throughs, but it is entirely separate from the game at hand, and leaves the player without contextual explanations for over half the included paintings. This leaves Monet: Le Mystère de l’Orangerie as a stark contrast to Mission Soleil: less calm, less visually exciting, less educational, less immersive. One cannot be consumed by the world as it remains in motion, be it through the introduction of actors, or the compelling of actions.

Conclure

With the advent of DVD-ROM and the proliferation of the Internet, the multimedia CD-ROM quickly faded into the annals of history, a short-lived flash in the pan of educational utopianism. Perhaps we were intended to fawn over these works in digital galleries delivered over a broadband connection. Perhaps the advances of computer graphics meant there was no need to rely on the crutches of pronounced art styles. Perhaps the call for more engaging gameplay forbade a slower, methodical approach. In any event, Night Café, Mission Soleil, and Monet: Le Mystère de l’Orangerie highlight a brief window of potential, quickly honed to an astounding apex, and just as quickly eschewed to deliver a ‘better’ product. Yet for their shortcomings, they represent possibility. A world in which anyone, anywhere could revel in the complexities of a turning point in art history, so long as they had a computer, a CD-ROM drive, and a polycarbonate disc acting as guide, teacher, and playmate. A world in which art is appreciated on its own merits, rather than as a stage for us to say we were there, surrounded by it yet blind to it all the same.

[1] Alexander Panetta, “A World of Art at Our Fingertips: How Covid-19 Accelerated the Digitization of Culture | CBC News,” CBCnews (CBC/Radio Canada, May 8, 2021), https://www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/digitization-culture-pandemic-1.6015861.↩

[2] “Show Me the Monet – Google Arts & Culture,” Google (Google), accessed September 3, 2022, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/yAUh79Qtnpb8bA.↩

[3] Brian Boucher, “’Emily in Paris’ Fueled a Frenzy for Immersive Van Gogh ‘Experiences.’ Now a Consumer Watchdog Is Issuing a Warning about NYC’s Dueling Shows,” Artnet News, March 16, 2021, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/immersive-van-gogh-better-business-bureau-1951887.↩

[4] Christina Morales, “Immersive Van Gogh Experiences Bloom like Sunflowers,” The New York Times (The New York Times, March 7, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/07/arts/design/van-gogh-immersive-experiences.html. ↩

[5] Jay Pfeifer, “’Immersive Van Gogh’ Has Upsides and Downsides, Explains Art Prof,” Davidson, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.davidson.edu/news/2021/04/16/immersive-van-gogh-has-upsides-and-downsides-explains-art-prof. ↩

[6] Anna Wiener, “The Rise of ‘Immersive’ Art,” The New Yorker, February 10, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-silicon-valley/the-rise-and-rise-of-immersive-art.↩

[7] “You Can Now Practice Yoga within the Immersive Van Gogh Exhibit in San Antonio,” KSAT (KSAT San Antonio, August 12, 2022), https://www.ksat.com/news/local/2022/08/12/you-can-now-practice-yoga-within-the-immersive-van-gogh-exhibit-in-san-antonio/.↩

[8] See J.R. Griffin, “Fine Art on Multimedia CD-ROM and the Web,” Computers in Libraries 17, no. 4 (1997): 63-67.↩

[9] Richard J. O’Connor, “Integrating Optical Videodisc and CD/ROM Technology to Teach Art History,” J. Educational Technology Systems 17, no. 1 (1988-89): 28-30..↩

[10] D.J.R. Bruckner, “CD ROM; A Gallery all to Yourself,” The New York Times, March 19, 1995, Section 7, Page 26.↩

[11] Miranda Haines, “CYBERSCAPE: The Virtual Art Museum: Culture at Your Fingertips,” International Herald Tribune, June 12, 1995.↩

[12] Jen, “Night Café,” Four Fat Chicks (Electric Eye Productions, March 13, 2002), http://www.fourfatchicks.com/Reviews/Night_Cafe/Night_Cafe.shtml. Steve Ramsey, “Night Cafe,” Quandary (August 2002), http://www.quandaryland.com/jsp/dispArticle.jsp?index=477.↩

[13] “I vincitori di Kid Screen,” Pc Open 46 (December 1999): 177.↩